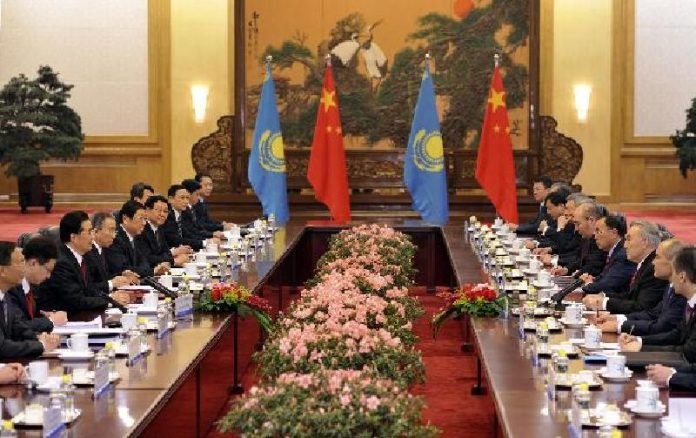

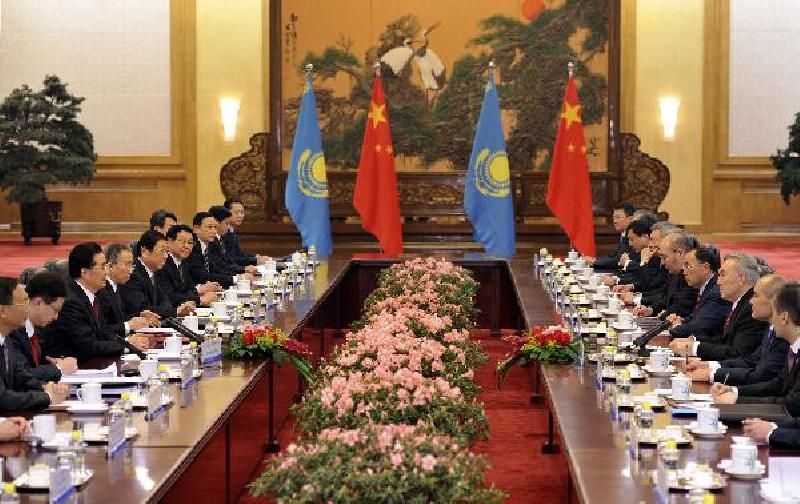

The visit of Xi Jinping, China’s president, to Kazakhstan last weekend and the signing of $30bn of new agreements is another symbol of the growing closeness between two of the world’s largest countries. It is a relationship built on mutual challenges, geographic proximity and energy, as China increasingly looks to central Asia to power its growing economy.

But these links have also raised alarm bells in the west. Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, the region’s main producers of oil and gas, have been warned against letting China dominate their economies. China has found itself accused of a modern colonialism as part of a new ‘Great Game’ and of plundering the natural resources of poorer, weaker countries.

From Kazakhstan’s perspective, such fears are badly misplaced. Our two countries have had warm relations for more than 20 years, fostered by close links at senior government level. We cooperate on a range of foreign policy issues, including through the Shanghai Co-operation Organization and the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia.

Economic ties have been driven by China’s need for energy and its willingness and ability to invest. China’s own oil fields can only meet half its needs, a figure expected to fall to 20 per cent by 2030.

China’s energy security concerns, however, rest as much on the location of supplies as on its need for imports. The country still depends on the politically volatile Middle East for nearly half its oil imports. The vast majority arrive by sea through the Straits of Malacca, which makes them susceptible to disruption.

This is why the opportunity to import energy overland from central Asia has proved so appealing. Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan can produce far more oil and gas than they need, with production set to soar. The giant Kashagan field in the Caspian Sea, in which it was announced last weekend that China was taking a stake, could catapult Kazakhstan into the top five global oil exporters

China has already invested significantly in building pipelines and in buying stakes from existing and new oil or gas fields. Oil first flowed along the Atasu-Alashankou pipeline to China in 2006. As the pipeline is extended, the annual capacity of oil export has been increased from 10m to 50m tonnes. China now takes 22 per cent of Kazakhstan’s oil exports.

Later this year, a new 3,000 km gas pipeline from Kazakhstan to Khorgas in Xinjiang will come on stream to supply China with, at first, natural gas from Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. More links are planned so that central Asia can play an increasing role in closing China’s energy gap.

Kazakhstan strongly welcomes this investment and China’s engagement. It provides new revenues and prevents Kazakhstan’s exports being dependent on pipelines flowing through third countries. In terms of wider foreign policy, China’s engagement also strengthens Kazakhstan’s ability to maintain good and balanced relations with all its partners.

The result has been a dramatic increase in trade between Kazakhstan and China. Between 2000 and 2011, for example, bilateral trade increased over 15-fold to $25bn in 2011. Increases in exports from Kazakhstan have been balanced by an even bigger rise in imports from China over the same period.

Fears of a Chinese stranglehold on the Kazakh economy are, however, well wide of the mark. The vast majority of Kazakh oil and gas will continue to flow west to Russia and onto Europe. The US is the largest foreign investor in Kazakhstan’s oil industry. The EU remains its biggest trading partner. Kazakhstan continues to import far more goods from Russia than China. Nor is there any sign of China wanting to use its economic muscle to exert control over central Asia.

But while China’s investment and involvement is welcome, the economic interests of Kazakhstan and China are not identical. China wants continued access to energy and raw materials. Kazakhstan – mainly through its sovereign wealth fund Samruk Kazyna – is already looking to how it can diversify its economy away from an over-dependence on the exports of its natural resources. Without care on both sides, these divergent interests could lead to tensions in future.

How can these tensions be avoided? China can help strengthen and diversify the Kazakh economy by supporting industrial development through joint ventures and the exchange of information and technology. A joint-enterprise agreement to manufacture telecom equipment in Kazakhstan last year showed the new way forward. At the same time, the moves announced by the Kazakh government to increase legal protections for outside investment – from China and from other countries – will help this process.

Chinese companies can also help build goodwill by playing a larger social role in local communities in Kazakhstan. The increased involvement in improving skills and supporting community initiatives by both domestic and foreign-owned businesses is a priority for the Kazakh government. There is plenty of room for new efforts to showing the benefits of China’s involvement in Kazakhstan and fostering cultural exchange between the two nations.

Increased and broader cooperation at regional and international levels will also help to defuse any concerns within Kazakhstan and from other partners. Such an approach would ensure today’s benign and bilateral relations continue and provide a model for successful relationships within and beyond the region of central Asia.

Dr Usen Suleimen is ambassador at large, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Kazakhstan. Dr Xiaojiang Yu is associate professor in the department of geography at the Hong Kong Baptist University.

This article is published with the support of the Sovereign Wealth Fund “Samruk-Kazyna” JSC of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

FINANCIAL TIMES, Sep 9, 2013